// Karen Turner, Ottawa Citizen

// Published on: April 2, 2015

Martin Bisson is a firm believer that good things come in small packages.

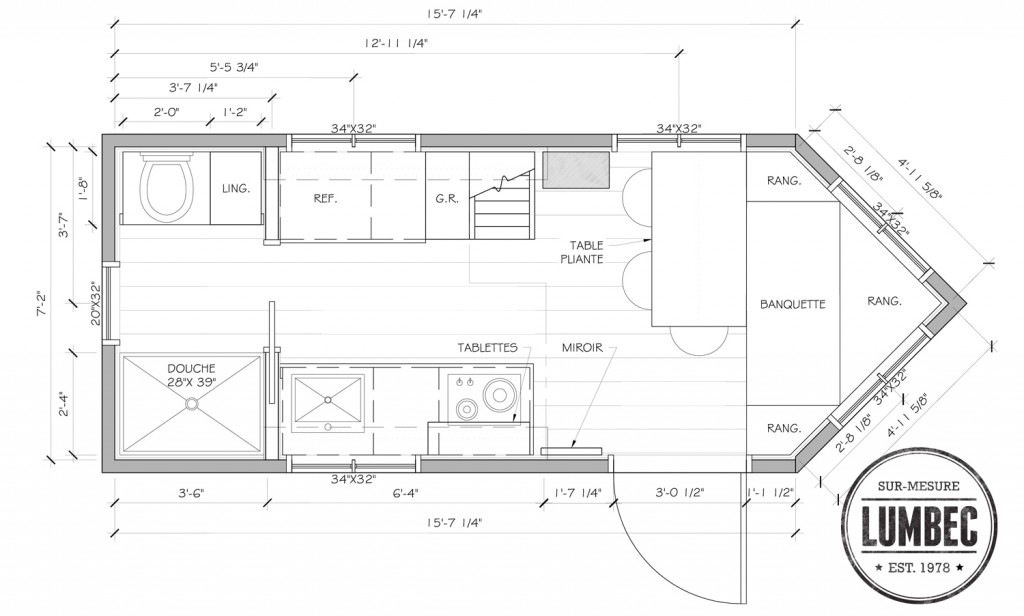

Owner of Lumbec, a small construction company in Aylmer specializing in garden sheds, gazebos and backyard decks, Bisson spent months fine-tuning the layout of the 225-square-foot prototype designed for a couple. Despite its compact size — it’s only 8.6 feet wide and 16 feet long — the skilled carpenter insists his house on wheels has all the comforts of a larger home.

“By building this prototype, we want to show Canadians it’s possible to live in a smaller house, but still have everything we need,” says Bisson, 36, whose design includes a loft bedroom with a king-size bed, a bathroom with a standup shower and a galley kitchen with a gas stove. “Our goal is to show what the size looks like.”

Bisson bought Lumbec in 2012 and was looking for ways to expand from a seasonal to year-round business when he became intrigued with the Tiny House Movement, a growing trend towards smaller living spaces sweeping across the United States.

The reasons for abandoning McMansions and downsizing to homes as little as 100 square feet are many: they’re cheaper to buy, heat and maintain, reduce your carbon footprint on the planet, and they simplify your life since there’s no room for clutter or hoarding extra stuff. The concept has yet to catch on in Canada, but Bisson hopes to change all that.

“The possibilities are endless,” says the father of three, who can see tiny houses also being used as cottages, bunkies, guest houses or offices.

Construction of the Lumbec Tiny House started in February inside the company workshop in Aylmer’s industrial park. Once the floor and exterior walls were attached to the custom trailer frame and the roof was installed, the house was moved outside, where Bisson and his carpenters have been working many long hours and weekends to complete the project in time for the cottage show, April 10 to 12 at the EY Centre in Ottawa.

“We set the bar pretty high,” admitted a weary Bisson of the hectic two-month construction schedule during a recent tour of the home’s unfinished interior. “But we are confident that we will reach our goal.”

To maximize the efficiency of the tiny design, every square inch of space has been used. Built-in benches at the front of the house conceal hidden storage and the dinner table doubles as a work space. Behind the ladder leading to the loft, there are open cubbies for storing books, hats and mitts or shoes and the armoire by the bed includes a built-in TV unit.

“Every object has to have more than one use,” says Bisson, who has also designed 24-foot models with a bedroom off the bathroom and a Murphy bed that turns into a desk when not in use.

Unlike mobile homes and recreational trailers, which Bisson says have about a 15-year lifespan before the roof starts to leak and mould sets in, the Lumbec Tiny House is built to last, using quality finishes and materials, many of which come from local suppliers.

The exterior is sided in stained pine and cedar shakes while the interior combines natural tongue-and-groove pine and reclaimed barnboard. Though not built to meet green specifications, the home features Energy Star windows and is well-insulated.

“Being small, it is already efficient,” says Bisson, who admits it wouldn’t take much to keep the tiny house toasty warm on a frosty winter night.

Canada’s cold climate is only one obstacle to selling the idea of tiny houses to buyers north of the border, where homeowners spend many months holed up inside their houses. Bisson, who has been blogging about the construction of the Lumbec prototype since Day 1, says the bigger challenge is convincing municipalities to change their zoning bylaws to allow the construction of micro houses.

In Gatineau, 527 square feet is the minimum size allowed for a single-family detached house, he says. There is no minimum house size set out by the City of Ottawa’s zoning bylaw, but Ontario regulations stipulate a studio must be a minimum 269 square feet, a one-bedroom unit 344 square feet and a two-bedroom 441 square feet, says Emily Davies, a planner with the City of Ottawa’s Planning and Growth Management department.

Davies says the city is conducting a study on “secondary dwelling units” as viable options for urban intensification. Current rules governing granny suites, basement apartments and “all forms of detached” houses are being reviewed, she says. The results of the study will be released in May.

“Tiny houses could be a viable form of intensification,” says Davies. “The study will consider all forms of detached dwelling units, assuming they conform to provincial regulations.”

John Herbert, executive director of the Greater Ottawa Home Builders’ Association, has been following the Tiny House Movement in the U.S. and says that although the City of Ottawa is a strong proponent of intensification, he doubts it would ever accept micro housing as infills.

“The neighbours would go crazy,” says Herbert of the public reaction to building tiny houses alongside much bigger homes.

When it comes to intensification, he says the more lucrative alternative is “to cram as many people into one dwelling.” He believes quality of life isn’t even a consideration. “It’s pure economics. Just stick them all in a highrise … it’s all cost driven.”

Bisson, who estimates his tiny house designs would cost about $200-a-square-foot to build, has approached several nearby municipalities, including La Pêche and Val-des-Monts, to sell the idea of building communities of tiny houses. He’s also been in talks with rural property owners interested in downsizing to smaller quarters.

“Whether on wheels or on a foundation, the Tiny House Movement is here to stay,” says the determined builder, who looks forward to getting feedback on his design from visitors to the cottage show. “We know there is a market for this type of housing.”